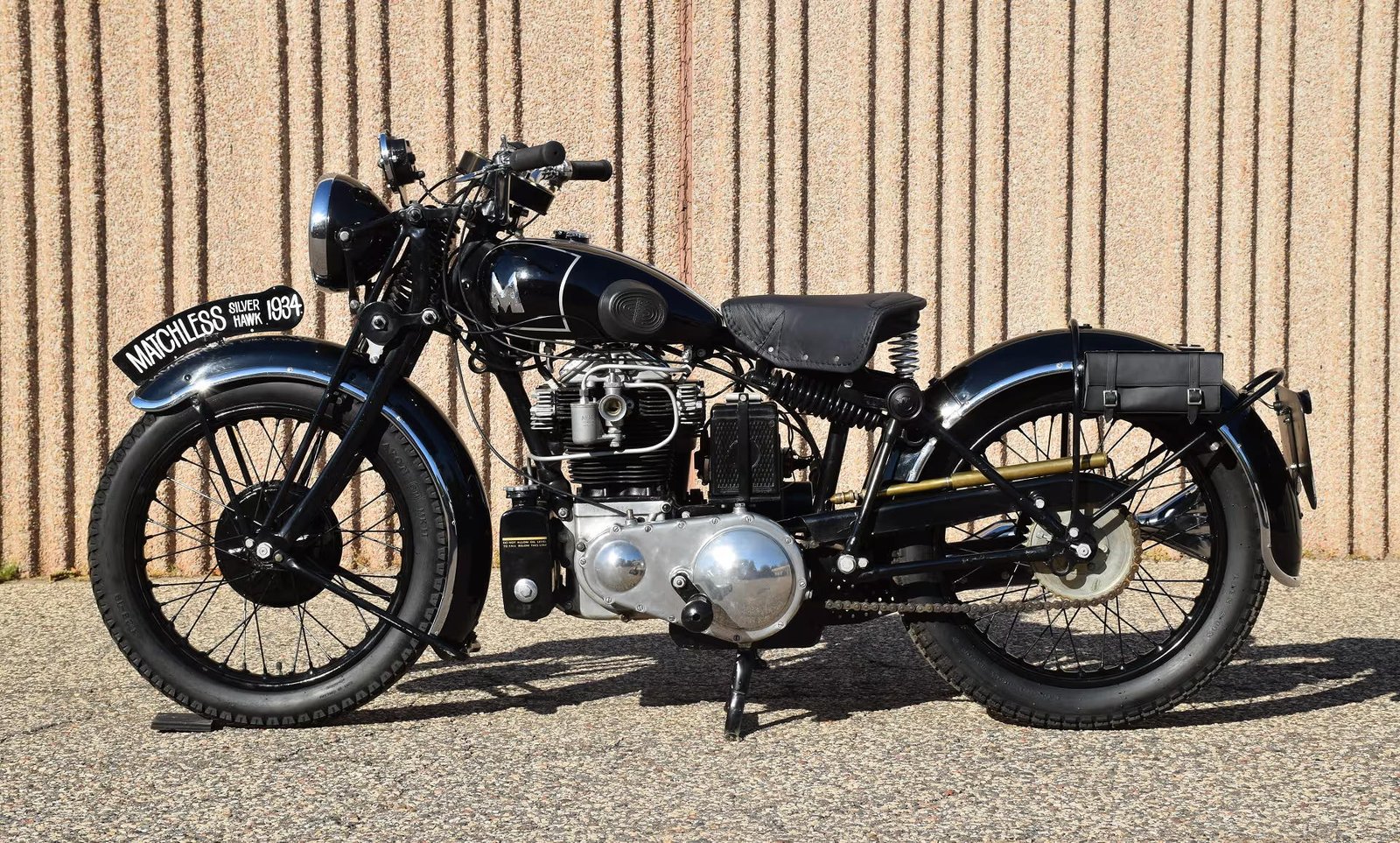

More than $60,000 for a Matchless! That’s the result from the Mecum classic mogtorcycle auction in Las Vegas in January. Well, it is a very special Matchless, a 1934 Silver Hawk V4 beautifully finished and with tons of provenance as well. But what is the Silver Hawk?

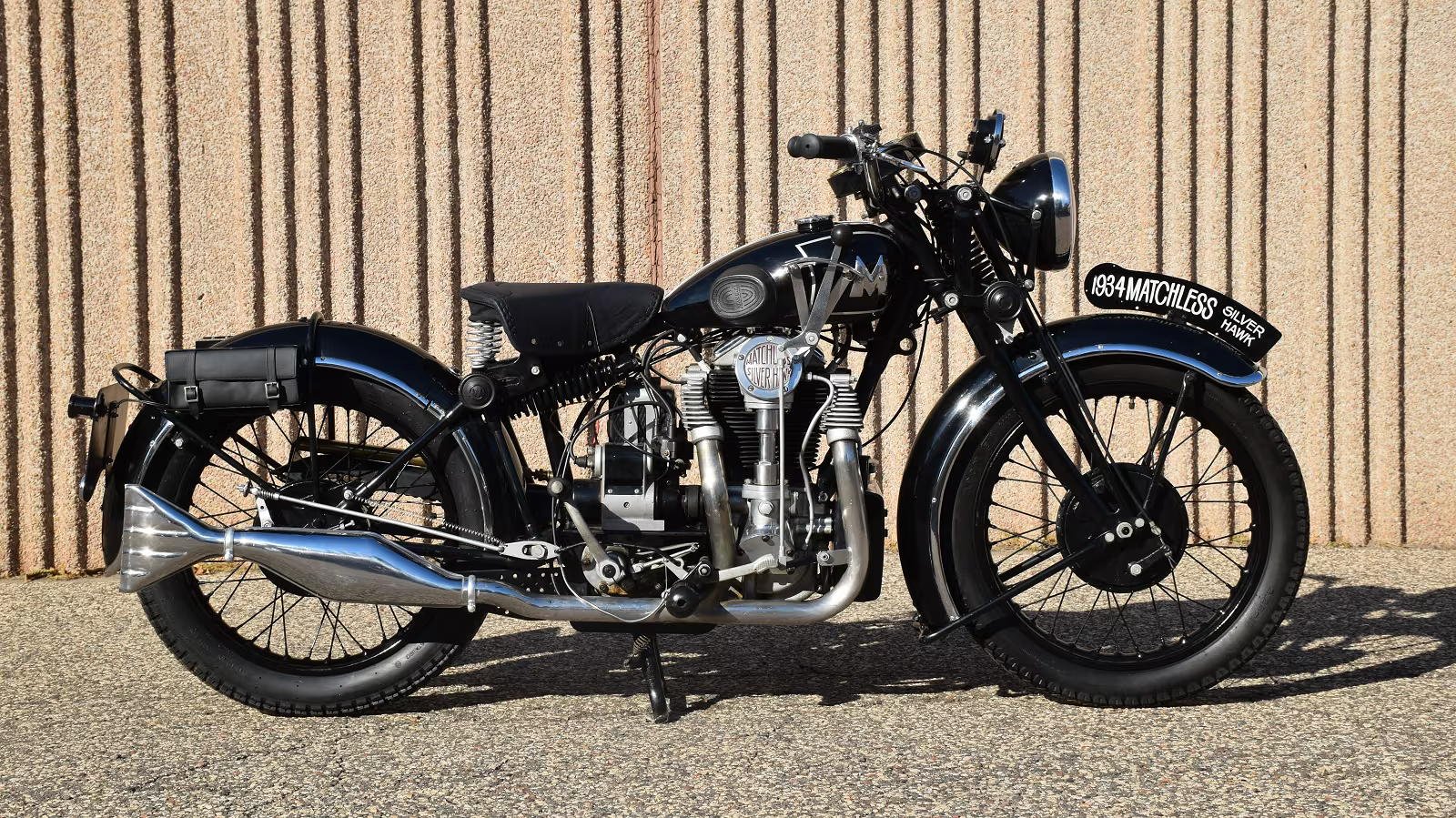

Back in the early 1930s, Britain was deep in the grip of the Great Depression. Prudence was fashionable, restraint encouraged. Matchless responded by doing the exact opposite. First came the Silver Arrow, then in 1931 the Hawk — a four-cylinder, overhead-cam luxury motorcycle intended to sit at the very top of the firm’s range. It was expensive, complex and utterly unapologetic.

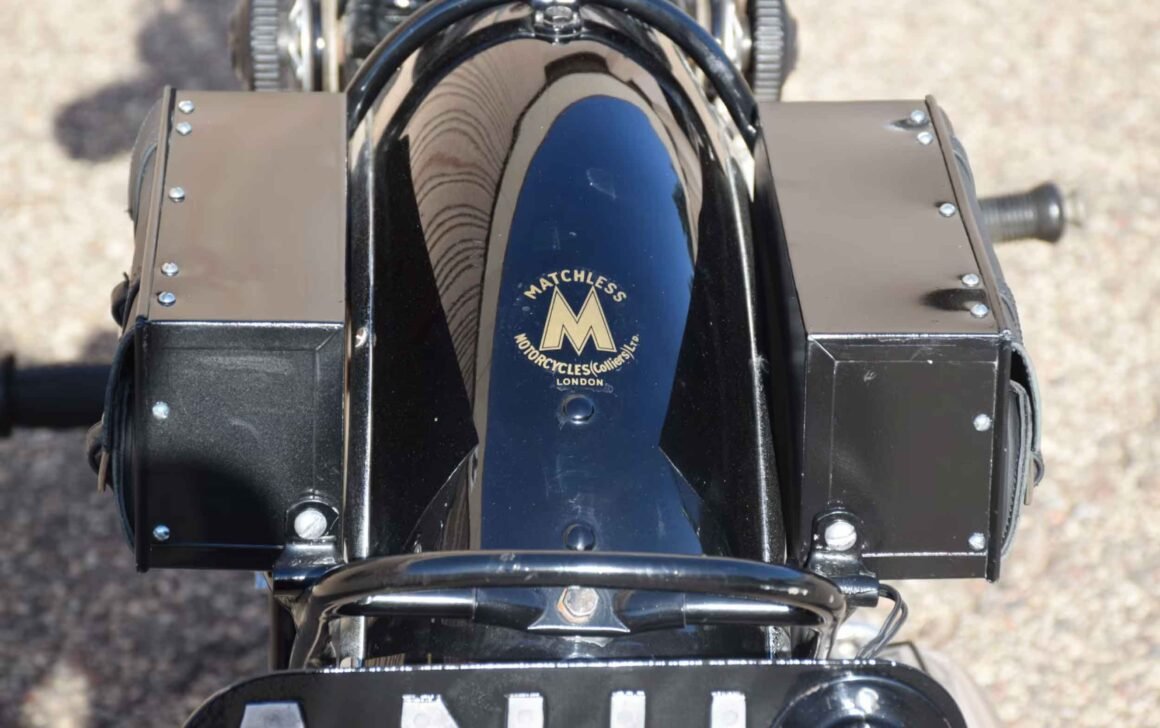

The Silver Hawk was the work of Bert Collier, one of the brothers behind Matchless and a man clearly more interested in mechanical elegance than balance sheets. The engine alone was enough to stop hardened riders in their tracks: a 593cc air-cooled V4 with all four cylinders cast in a single block, topped by a one-piece overhead camshaft head driven by bevel gears. Matchless claimed it was “absolutely vibrationless,” a bold statement in an era when most motorcycles rattled like a bag of nails.

Yet period road tests — and owners since — suggest it was no exaggeration. The Hawk would pull smoothly from walking pace to over 80mph in top gear, a party trick made all the more impressive by its hand-operated gear change. This was a machine designed to lope, not lunge, and to cover distance in dignified silence.

Production numbers were tiny. Most records indicate fewer than 50 examples of the 1934 Model B were built, and fewer than 70 Silver Hawk and Silver Arrow machines are known to be registered today. Expense was the enemy: the Hawk cost £75 new, more than many small cars, and around £5 more than its nearest rival, the Ariel Square Four. In purely commercial terms, it never stood a chance.

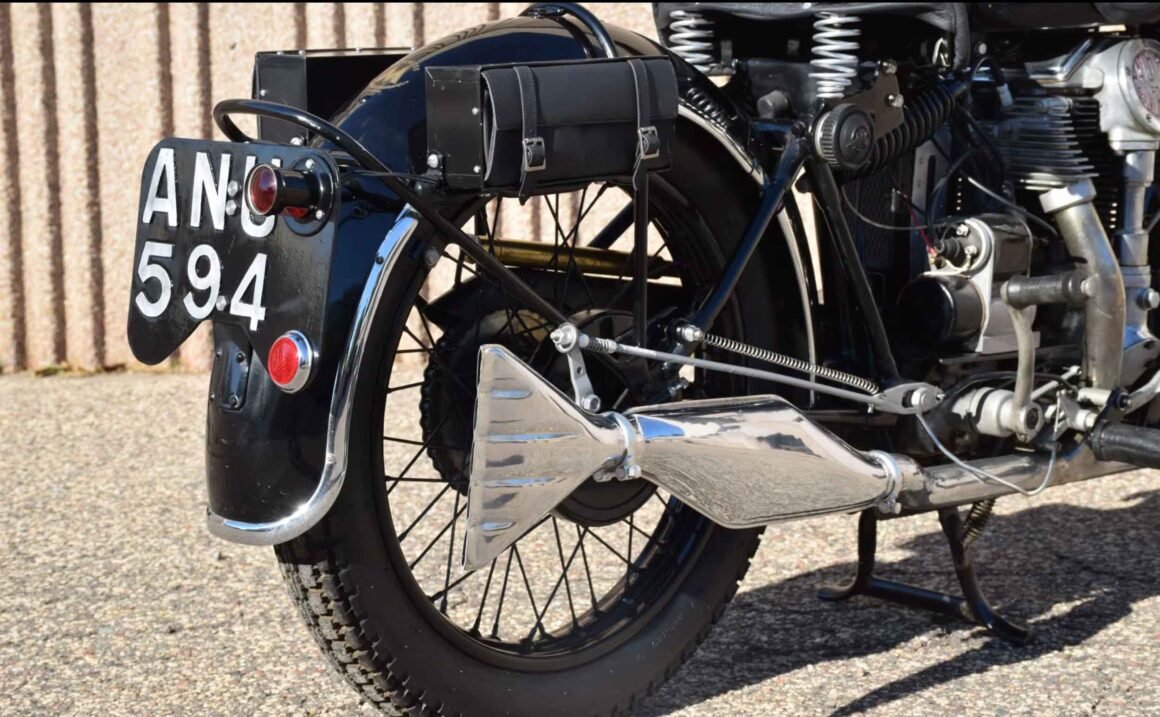

The example crossing the Mecum block this month is a 1934 Silver Hawk Model B, chassis number 977, engine number 34B1875. Finished in near-all black with delicate silver coachlining and restrained chrome, it presents exactly as a Silver Hawk should: imposing, elegant, and faintly aloof.

It has been sympathetically detailed by its current custodian, Dave Moot, former president of the Viking Chapter of the Antique Motorcycle Club of America, who acquired the bike from an Australian private collection in 2004. Original paperwork, period magazine features, and registry listing accompany the machine, lending welcome substance to its already considerable presence.

What makes the Silver Hawk so fascinating is not just its rarity, but its attitude. This was not a racing motorcycle, nor a practical commuter. It was a statement — that a motorcycle could offer the smoothness, silence, and refinement of a luxury motor car without sacrificing performance. Matchless even claimed it could be started by hand on the kickstarter, such was the engine’s flexibility.

Production ended quietly in 1935. The Hawk was simply too expensive, too complex, too good for the world it found itself in.